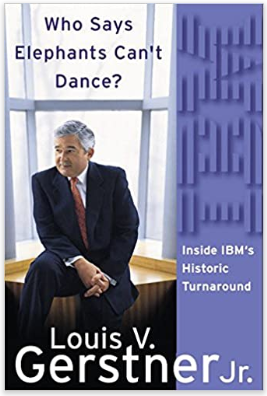

Jr, L. V. G. (2002). Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?: Inside IBM’s Historic Turnaround (First Edition edition). Harper Business.

Until I came to IBM, I probably would have told you that culture was just one among several important elements in any organization’s makeup and success—along with vision, strategy, marketing, financials, and the like. I might have chronicled the positive and negative cultural attributes of my companies (“positive” and “negative” from the point of view of driving marketplace success). And I could have told you how I went about tapping into—or changing—those attributes. The descriptions would have been accurate, but in one important respect I would have been wrong. I came to see, in my time at IBM, that culture isn’t just one aspect of the game—it is the game. (emphasis mine)

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

This has been an unexpectedly difficult text to review, due to several factors. Full disclosure: I work @IBM and I’ve been an IBMer for the last 10 years of my life. And I work directly with culture at IBM, being it Agile methodology, Mindfulness or Storytelling. Therefore, while I have a lot of hard-won insights of the struggle of cultural change at IBM, I also have probably a very strong bias. Also, some things seem discouragingly similar after so long. But when Guillermo García (the CIC visionary leader and probably one of the most committed people that I know for cultural change) asked me to include this book and the next on the review list, I told him that I would try.

Things has been…challenging.

Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?: Inside IBM’s Historic Turnaround Is a book by Louis V. Gerstner Jr., the CEO who essentially changed IBM’s profile and saved the company from fragmenting into small shards of a once imposing empire on IT. One of the major challenges on reviewing this book is its disorganized structure: it’s nor a journal of the experience, an argument for the politics or strategy of the change or an analysis post-fact, but rather a combination of all of it. It starts on the biography of the author, walks you through his first days at IBM in an hour to hour fashion, then jumps into the following years and ends explaining both the trends that the author predicted and does some financial analysis. That so schizophrenic a structure is understandable is due to the strong voice of the author, who is witty and self-effacing enough to admit the problems firsthand

I wrote this book without the aid of a coauthor or a ghostwriter (which is why it’s a good bet this is going to be my last book; I had no idea it would be so hard to do).

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

Since it is difficult to implement a succinct analysis of the book given its structure and lacking the wit of the author, I’ll try to summarize the main points at each part of the book and then do a final analysis at the end.

The beginning: bio and the choice to become CEO

The author begins with a quick story of himself; coming from an upper-middle class upbringing, he, interestingly is a graduate from both Darthmouth College and Harvard. His first job is an executive consultant at McKinsey; then he moves to become quickly CEO of Nabisco, of Amex and other major companies, until he’s approached in December 1992 to become CEO of IBM. At first, he’s reluctant but eventually agrees when it’s clear that he’s the main candidate. Then he presents a story of the company starting with Thomas Watson; there’s no mention of the issues and the existence of IBM before him nor the troubling time at the 40’s. The author’s main question at this point is: how a company that in 1990 had the most profitable year ever can be almost bankrupt in 1992?

New CEO

There was no computer in the CEO’s office.

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

Essentially, the author then takes us on a detailed journey of his first year as a CEO (to the level when, at the start of the part, the first week is recounted almost in an hour to hour basis). One of the first people he meets with is his brother, who was an executive at IBM before having to retire due to Lyme’s disease (he later says that he feels the brother provided the best advice overall). He meets with luminaries of the IT field (the meeting with Bill Gates goes specially badly) and clashes with the established IBMers. What he finds, however, is dauting:

For me at IBM this meant, in some respects, seizing the microphone from the business unit heads, who often felt strongly about controlling communications with “their people”—to establish their priorities, their voice, their personal brand. In some companies, at some times, such action may be appropriate—but not at the Balkanized IBM of the early 1990s. This was a crisis we all faced. We needed to start understanding ourselves as one enterprise, driven by one coherent idea. The only person who could communicate that was the CEO—me.

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

(as an aside, I’ve heard “balkanized” as a term for IBM more times that I can count)

He then goes to meet with most high-level managers in the company, including next CEO Sam Palmisano, from sales. But his most impactful encounter is with Thomas Edison Jr, whom with he shares a ride and a talk about “our” company.

The main issue that he finds, in Agile terms, is that there’s no space for value. The client does not have a voice at all. All IBM wants at the time is to lock down customers and then, essentially use them to pay an ever-growing, bureaucratic structure. There are no PO, no stakeholders looking out for value.

The author’s greatest genius, in our opinion, is his outsider perspective and his unshakeable conviction that he was the only man fit for the job. He recognizes that splintering IBM will give away its greatest leverage, the size at the same time that he recognizes how difficult the size itself makes the transformation possible. Therefore, he starts a series of shocking, short-term actions to ensure the life of the company.

The first year ends with him, reflecting on the fact that both he and the company survived what was almost certainly a death trap. Now, he has to figure what to do next.

From ’94 to 2002

From then on, the narrative becomes jumpier: it can both change years from chapter to chapter, but it also can change from a journal of the year to a defense of a strategic choice.

It would be difficult to summarize it at, but essentially, the author’s choices as CEO was to put business value over almost every other priority (he keeps funded the research wing, despite not being directly business dependent, because he sees it as a strategic differentiator). He fires thousands of employees, reorganize all the systems of governance and promotes business administrators and sales over tech specialists.

They included a general disinterest in customer needs, accompanied by a preoccupation with internal politics. There was general permission to stop projects dead in their tracks, a bureaucratic infrastructure that defended turf instead of promoting collaboration, and a management class that presided rather than acted. IBM even had a language all its own. This isn’t to ridicule IBM culture. Quite the contrary, as I’ve indicated, it remains one of the company’s unique strengths. But like any living thing, it was susceptible to disease—and the first step to a cure was to identify the symptoms. The Customer Comes Second

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

Recognizing the value of the Mainframe, he streams and lowers the price of it to increase market share. He changes the philosophy of most of the company towards that of a Service company, understanding that the client may not want to be locked by having every single app or server be from a single company, but that someone still has to do that connection.

By 1996 I was ready to break the services unit out as a separate business. We formed IBM Global Services. The change was still traumatic for some of our managers, but it was eventually accepted as inevitable by most of our colleagues.

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

He invests in a consolidated marketing strategy (there wasn’t a marketing department with systematic training, the author notes), he does away with inefficient products (like Os/2 Warp) because he values Customer Experience over technical details.

With os/2-the fallacy that the best technology always wins. (…) So we came to the OS/2 v. Windows conformation with a product that was technically superior and a cultural inability to understand why we were getting flogged in the marketplace. First, the buyers were individual consumers, not senior technology officers. Consumers didn’t care much about advanced, but arcane, technical capability. (…) Second, Microsoft had all the software developers locked up, so all the best applications ran on Windows.

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

Essentially, he understands the client’s point of view well enough to empathize and direct the strategy towards the greatest value.

In the case of application software-the myth of “account control.” This was a term used by IBM and others to talk about how a company maintained its hold on customers and their wallets. As a former customer, I was always offended and indignant that information technology companies talked about controlling customers.

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

The book ends with his farewell address and a financial analysis that shows how much more profitable IBM was under his leadership.

Analysis

As we mentioned in the intro, this was a difficult book to analyze, due to its changing structure (it is written like a blog post storm, before blogs) and both its greatest strength and weakness: the unique authorial voice.

On one hand, the author is witty, funny and very engaging. His points (disorganized as they are) tend to be clear and succinct. He has complete conviction: he must have been a terrific business speaker. His ideas of making the company more Lean, Agile and oriented towards Value…make perfect sense in an Agile world, 25+ years later. His experience as a CEO and a client makes his extremely valuable to deal with other CEOs and clients. He’s like the Ultra-PO.

On the other hand, it is clear that the author, although he considers himself a humble businessman, is anything but. Not all businessmen come from Harvard. He never had any job lower in the totem pole than executive and most of his life he’s been the CEO. While he works on an IT company and he deals with IT People, it’s made very clear in his writing that there are Leaders (with a capital L) and then there’s everyone else. When he makes himself available to be criticized via message, he’s almost in rage when someone does:

One employee, even as his employer was burning and sinking to the delight of our competitors, had the time and inclination to critique my entire visit to an IBM facility (…)

Sometimes I had to bite my tongue—almost in half. All I can say is, it was a good thing for some people that I was too busy to reply to all my e-mail!

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

This is somewhat compounded by the fact that he clearly believes in both dynasties and that he was the only person fit for the job; only his elder brother, sadly incapacitated by Lyme’s disease would have been an alternative. This total conviction on himself, making himself essentially the next big CEO after T.Watson Jr. does tend to run counter the Agile and Lean mindset of empowering others and being transparent and accountable.

But perhaps because of the year he took office on, perhaps because of the challenges and perhaps even because of this almost psychotic belief in his own value and incredible self-confidence, the author accomplished something no one believed it was possible.

Their book concluded that “the question for the present is whether IBM can survive. From our analysis thus far, it is clear that we think its prospects are very bleak.” (…) Even The Economist—understated and reliable—over the span of six weeks, published three major stories and one lengthy editorial on IBM’s problems. “Two questions still hang over the company,” its editors wrote. “In an industry driven by rapid technological change and swarming with smaller, nimbler firms, can a company of IBM’s size, however organized, react quickly enough to compete? And can IBM earn enough from expanding market segments such as computer services, software, and consulting to offset the horrifying decline in mainframe sales, from which it has always made most of its money? “The answer to both questions may be no.”

(Gerstner Jr, 2002)

So, my final review is: it is a very strange book. Almost a blog before the blog, it tells a valuable story on how one man changed a culture. We might take away his relentless focus and learn a lot about the almost LEAN way that the author approached his objective; and while his voice might be troubling, specially with some contradictions that glare specially in today’s Agile workplace, we would remiss to not say that despite all, the author’s immense confidence in himself was, actually, merited and he was the Right Man for the Job. His story is convoluted, changing and genial, but never dull.