(all media is from the great book “Storytelling for User Experience: Crafting Stories for Better Design” – Whitney Quesenbery & Kevin Brooks (2014)Rosenfeld ed. )

I have been, of late, promoted to (drum roll, please!) Global Leader of Business Storytelling at IBM.

Now, this is one of those Linkedin updates that, besides the usual congrats tends to generate questions; questions that, like a bad case of political commentary can be boiled down to, basically, just one question.

“What’s that thing, Storytelling”

So I tell them; “I help people tell stories about what they want, to craft stories with meaning and emotion. And that helps them work and communicate better”.

And almost always, there it comes. Like the tide, like taxes, like the next big thing that ends up just like the old, tired thing. The follow up question. “Oh, can they just tell you the requirements? It’s not a big deal…they can tell you what they want and you can go work on that”.

Oh, sweet summer child; the winter of a client’s discontent has not wilted thee yet, but it will come to pass.

Any of us that has worked for some time in Scrum remembers when we called the User Stories “Backlog Items”. Why did we make the switch? Why don’t we call them requirements anymore?

Let me answer this with another question.

Who remembers Claude Shannon?

This dapper gent right here

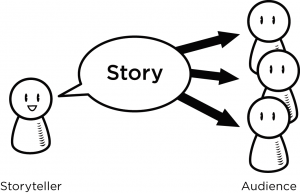

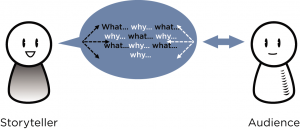

So Claude Shannon, mathematician, engineer and the motherlovin’ Father of Information Technologies (Hi, dad!) thought that a story was, essentially a way to move a message from one place to another. That is, he thought of stories as quintessential data carriers.

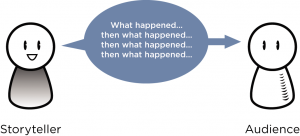

In his view, that for a lot of years has been the default, when a client talks to a developer he only transmits flawlessly information, and just information about a rational decision that he or she has made and how he or she came to that conclusion.

And yet…has any of us that has truly worked on development had a case like this? I suspect not. Let’s talk, for example, about the Online Prospectus.

The Open University (http://www.open.ac.uk/) is the largest University in the UK. In order to enroll into a course, you have to go through an Online Prospectus (https://www.open.ac.uk/request/prospectus). When they designed that part, they just offered a course listing.

After some time, the people from OU found out something strange: they had the largest rates for enrollment in the UK…but also the largest drop rates. So, they thought, perhaps we haven’t included enough information. So they modified the Prospectus…but still, they found the rates unchanged.

So they did something truly revolutionary: they talked to the prospective students.

And when they talked, the OU people found out, firsthand, that the students weren’t interested as much in pure info than in how the courses aligned with their dreams and hopes. I don’t care as much for a course, they said, as long as it is a path for me to be a banker/footy player/shipwright, etc.

They also talked with dropouts. Like Priti, a Pakistani woman who had enrolled into an English course after she had put his career on hold to raise a family. But being a Pakistani emigré had its challenges, challenges that weren’t being met by a course listing. On how many courses is there a “Are you an immigrant from a former colony from South Asia?” check-box?

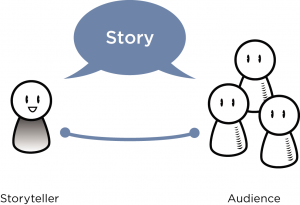

So what they do now, what they have found out keeps the best enrollment rates but reduces the dropout rates to almost nothing is…they talk to people. Just that. They hear the prospective students; they listen to their dreams and expectations. They have found out that they have to engage in the level of emotions and sell them into an idea before talking courses. And that they have to empower the student to be the co-creator of his or hers career path.

This is done via understanding the requirement of the student and the realization that a story is not something that moves information from a place to another, but rather a co-creation.

And yet…we know this. At some level, we know it. But we don’t use it in the traditional development approach.

Let’s say that you want to take a date to a fancy dinner. Not just fancy, but downright swanky. You find out the best place, a new place that you’ve never been into and make a reservation in advance; you fix your hair and meet your date at the door in your best clothes.

You are an Ace, that night. Witty and charming, you make small talk with the Maitre D’ and the waiter. Everyone is pleased, everyone is charmed. The wine, entrée and dinner menus are brought to you.

Now, at this point…do you just wave them down and say “I know what we want. Give us two burgers, medium rare, some fries and two Coors light, please”?

Of course not; you browse the menu. The Maitre might ask a quick question and offer a suggestion. You will review it and think how this is fitting. Perhaps the wine is white: should we have seafood? Or is it a deep red and some savory meet? What will we have for dessert? What will we have with dessert?. You decide based on a series of feedback clues and your own desire.

This situation is analogous to a development project. If you go into a restaurant, of course…you want to be fed. This is the general requirement. But what, how and in which order is not a given. Your date preferences, your own, the specialty of the house, what you will be drinking…the specific requirements will not be set in stone beforehand you walk into that place. It will be constructed by a dance of factors and will be rechecked at each course (if the Maitre is good) for feedback. While we know that we want to have a memorable dinner, we don’t know exactly what we will get; and that finding out is what makes it great. The story not only provides pure information, but also motivation and context: what are we looking for?

And yet…when we expect to work in something much more complex than a dinner, something as complex as a development project…we assume more and have less time and interest than when we go to a fancy dinner. We end up ordering burgers, all the time and then complaining that they weren’t as good as McDonalds. We have to get to grips that while we can have a general idea, this is more a framework than a real requirement. The specific needs to be worked on, distilled like a good whiskey from the malt.

And the distillery is the Storytelling act. If you don’t think that it is important…try drinking dried malt.