Man thinking, by Degás

Let’s dive a little bit deeper. How can we use Storytelling for something concrete? Say: how can we do Storytelling to reduce the cost of bringing up to speed a new team member who’s fresh from the street?

So, let’s think about the cost. Suppose that we bring someone right from the street into an established team. Let’s assume (I know, mother of dragons and disappointments, but let’s anyway) that the HR folk and that the person is neither a junior and that he or she has the skills needed for the job. What’s the main cost, then, that is incurred?

Mostly, I think, is getting him or her to have a transmission of experience.

What experience? The experience of that particular work and workplace. Because we love to think in abstract levels, every workplace and every team seems interchangeable. But anyone who has worked deep in delivery knows the truth: each team, like each project is a relationship. And like any relationship, it takes time and effort to get accustomed. Hence, the cost of getting someone to speed.

So, let’s again focus deeper. What is experience and how do we go about getting it?

Let me share how I got the insight on experience that I use at work. When I was young…or less old, anyway my first corporate job was in the worst of the worst areas: Development support. This was a job that theoretically entailed giving guidelines and best practices to programmers. But it practice, we were the Fire Department: we usually got involved in a project when it was just on the deadline and we need it online within a short timeframe. If you’re thinking that’s not a job for a rookie you would be absolutely correct. But it was a consulting manpower firm, there was a place open, and that was that.

So I tried not to flounder and was helped by this twenty seven year old guy, who at that time seemed to me to be the veteran of a thousand psychic wars. He told me, one night when we were staying trying to get some C++ code working “be glad, kid…this is the only thing to do. Yo do something and gain experience…look at me, I’ve been doing the same thing for the last three years and I know exactly now where the devs will have their bugs”.

While I appreciated his kindness and the interest on training me that he had, that answer bothered me for a long time. If you know where the bugs are…what are we doing trying to search for them at one in the morning? Also…why don’t you go beforehand to the devs and tell them? Those questions went back and forth in my head, until I realized what was the problem.

He was doing things but he wasn’t using that doing to really gain experience.

And that’s where I understood something about experience. For me, experience requieres doing; no two ways about that. You cannot be experienced in something until you’ve done it enough. But just doing is not sufficient. You have to reflect on what you’re doing and specially why you’re doing in order to compare the result of that particular case to the ideal outcome. You have to do, to measure and to adjust or improve.

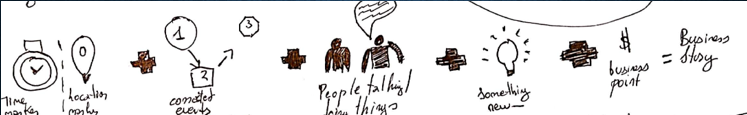

So, for me, the formula is

EXPERIENCE = DOING + REFLECTION

Ok. So…how do we reflect on something, within, say an Agile Framework?

Let me introduce you to the

Agile Retrospective

A Retropective is a ceremony, a part of the Scrum Process that is executed each and every iteration, just at the end. The main objective of an iteration is to generate a reflection on how do we work. And this reflection is a vital part of the work. This is how we gain experience.

A retro essentially has two roles

- The team members who have worked

The facilitator (usually a Scrum Master, but anyone can do it)

It is alloted between one or two hours of time, on the last day of iteration. If the iteration is two weeks long, it is done usually in one hour. If it’s longer, you allot half an hour per week.

The mechanism of the iteration is very simple. The facilitator opens the meeting and asks everyone to reflect on the iteration that just finished. Then he asks three simple questions:

- What should we Start doing? What we would have been better served doing before and we need to formally include in the process? For example, does the client always have a delay in testing, so we have to factor it on estimations? Or perhaps do x stakeholder never comes to the meetings, so we need to establish a formal escalation channel for her?

- What should we Stop doing? What do we do that makes no sense or actually hurts our work? For example: do we have meetings that we can pare down or eliminate entirely? Are we doing documentation for its own sake?

- What we should Continue & Emphasize? For example: the Retro meetings are producing great experience. Shouldn’t we emphasize them and include more people so they become better known?

The way that this is done varies: some people use a “just shout what you want to say” approach. Some people use an object to designate a speaker (usually a rubber ball) where one can solicit from another team member at any time. Another way is to do a round, member by member. Yet another is to do an anonymous proposal in three jars, one for each category. It varies: personally I usually go by the ball approach and perhaps a member by member if that’s not working, but it depends on the team. This I let run for about 3/6th of the meeting’s time.

Image by Mountaingoat Software

After the part where we reflect, then we do a vote. Each person usually votes the most important item on each category or, if there are a lot of them, we vote the first three. That takes 1/6th of the meeting time.

The last part of the meeting is bringing out something where all the results of previous Retros are kept. I usually call it the Black Bible because I tend to use black notepads, but it can be an Excel, a Word file, etc. We enter the picked things into it, and we quickly go over the previous items on each category asking ourselves: have we kept what experience we had in our minds? If we thought that we should stop doing X two retros ago…have we really stopped or we need to again bring it to the forefront? This adding of the new items and review of the old usually takes 2/6th of the meeting’s time.

And that’s the way to generate experience in a group via Retro.

Storytelling comes in

Ok. So you got the why it is good to create experience and the how to create experience in a group. How does this translate in a reduced cost for a new member in a team? How do you transmit the experience of the group, that resides on its Black Bible to the new member?

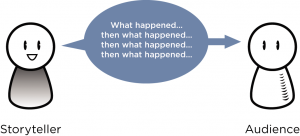

The way it would have been done when I started working was depressingly literal: I usually was sat in a workstation by the team’s lead and given some documents, without context, to read. This was a very, very inefficient way: first I had to discover what the project was about. Then I had to understand the business side of it. Then, I had to start putting faces, names and roles together. Then I had to start going to meetings, hearing terms being discussed for current functionality and try to tie them in my own to the documentation, which by that point was probably outdated…and so on. I took in some cases months until someone was up to speed.

Imagine that you’re starting a project and are given its Black Bible. Probably it is full of annotations that doesn’t mean anything to you, like “We have to engage Larry two weeks before sending it to Mary” or “Need to emphasize clearing standards with John’s dept”. What does that mean? Who are these guys? How does that relate to the project?

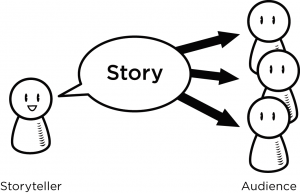

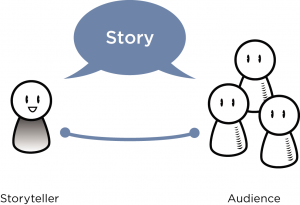

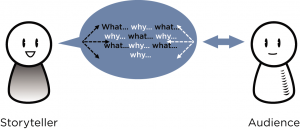

And now, imagine something else. Imagine that someone takes the time to craft a small Business story for each one of the different parts of the project. An overarching story: what are we trying to do and why. Some small stories (called Clarity Stories in our framework) that talk about departments, roles, modes of work. Some stories that explain why we did what we did: these are called Solution stories…and so on.

This, of course, meant that there will be someone crafting these stories and someone tasked to tell them to a new arrival. This will take time, of course. In one case, for example, it took me about one full day to both tell the stories and answer questions about them. One full day + time to write and craft them…say…two more days.

Three days total…vs months?

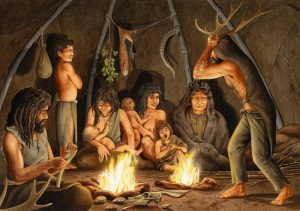

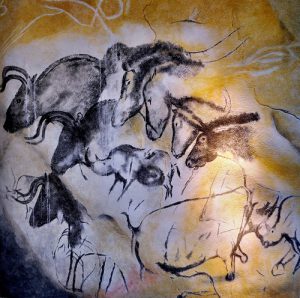

I’m not claiming that crafting a story will make any person be ready to work as soon as three days. But here’s what I know: stories provide meaning and are memorable. How much more memorable is a well crafted story that a sheaf of documentation? Try it by yourself: who among those that are reading this can bring to mind the plot of the Red Riding Hood? The acts of the Story? The characters?

Ok, now try to remember the table of contents of the documentation for a project a couple of years back. The modules? The org chart?

Stories are more efficient. They excel at transmitting experience by co-creating it with their listener. If we use them alongside methods for gaining experience, the resulting accelerator will both reduce our cost and create a richer, more meaningful experience.

So now you know the why, the how and the way to measure it. Let’s give it a try!