I’ve been writing quite extensively around and about the SAFe framework. Of course, finding out about SAFe is as easy as going to https://scaledagileframework.com/ .

Now is especially a good time, since SAFe 6.0 has just launched.

So why I have spent as much time as I have writing this article? Because the SAFe site, while full of information is… extremely full of information. Not to mention acronyms; SAFe uses acronyms the way you breathe after a lengthy immersion underwater. It is a complex, established methodology.

This complexity obscures the main questions you should be asking, for a Digital Transformation: What is SAFe? What are the challenges in a SAFe transformation? How does an SAFe Enterprise looks like?

And the main question: should I use SAFe?

Join me into this exploration into SAFety.

What is Safe agility?

Safe agility, often referred to as “SAFe Agile” or “Scaled Agile Framework,” is a set of principles, processes, and practices designed to help large organizations adopt and scale Agile methodologies to improve software and systems development. SAFe Agile provides a structured approach for implementing Agile practices across multiple teams and departments, enabling them to work together effectively and deliver complex projects more efficiently.

The framework is based on several core principles, including Lean, Agile, and Systems Thinking, and it provides guidance on roles, responsibilities, artifacts, and events necessary for implementing Agile at scale. Some of the key components of SAFe Agile include:

· Agile Release Train (ART): A cross-functional group of teams that work together to deliver a continuous flow of value by developing, testing, and deploying software increments.

· Program Increment (PI): A timebox of usually 8-12 weeks, consisting of multiple iterations (usually 2-week Sprints), where ARTs work together to achieve their objectives.

· DevOps and Continuous Delivery Pipeline: A set of practices and tools that enable teams to integrate, test, deploy, and release software rapidly and reliably.

· Lean Portfolio Management (LPM): A strategic approach for aligning an organization’s vision, strategy, and investment priorities, while effectively managing the flow of work.

· Innovation and Planning (IP) Iteration: A dedicated timebox for teams to focus on innovation, planning, and continuous improvement activities.

· SAFe Core Values: Built-in Quality, Program Execution, Alignment, and Transparency, which are the foundation for the framework and guide decision-making.

SAFe Agile has been adopted by many large organizations to help them scale their Agile practices, improve collaboration, and deliver value more rapidly. However, it’s important to note that SAFe is just one of several frameworks available for scaling Agile, and organizations should carefully consider their specific needs and contexts when choosing the right approach. Right now, SAFe is the one people know the most; so if finding skilled resources is an issue, SAFe might be the right choice based on availability of knowledge and experience.

Why should you use safe agility?

Organizations may choose to adopt SAFe Agile for a variety of reasons, depending on their specific needs and objectives. Here are some common reasons why organizations might choose to use SAFe Agile:

· Scalability: SAFe Agile provides a structured approach for scaling Agile practices across large organizations with multiple teams, departments, and layers of management. It helps address the challenges that arise when coordinating the work of multiple Agile teams working on large, complex projects.

· Alignment and collaboration: SAFe Agile promotes alignment and collaboration between teams and stakeholders at various levels of the organization. This helps ensure that the organization’s vision, strategy, and investment priorities are in sync and that everyone is working towards the same goals.

· Faster time to market: By implementing Agile Release Trains (ARTs) and Program Increments (PIs), SAFe Agile enables organizations to deliver value to customers more frequently and predictably. This can help organizations reduce time to market and stay ahead of their competitors.

· Improved quality: SAFe Agile emphasizes built-in quality, ensuring that quality is considered at every stage of the development process. This can result in reduced defects, lower rework, and improved overall product quality.

· Better risk management: SAFe Agile encourages early and continuous integration, testing, and feedback, which allows organizations to identify and address risks sooner in the development lifecycle. This can lead to more effective risk management and better decision-making.

· Flexibility and adaptability: SAFe Agile promotes a culture of continuous learning and improvement. This helps organizations become more adaptable and responsive to change, allowing them to better cope with the uncertainties and rapid pace of today’s business environment.

· Lean Portfolio Management: SAFe Agile’s Lean Portfolio Management (LPM) practices help organizations prioritize and allocate resources more effectively, ensuring that they are investing in the most valuable initiatives and maximizing their return on investment (ROI).

While SAFe Agile can offer many benefits, it’s important to note that it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. Organizations should carefully evaluate their specific needs, context, and existing Agile practices to determine whether SAFe Agile is the right fit for them.

How to transition organizations from traditional to SAFe

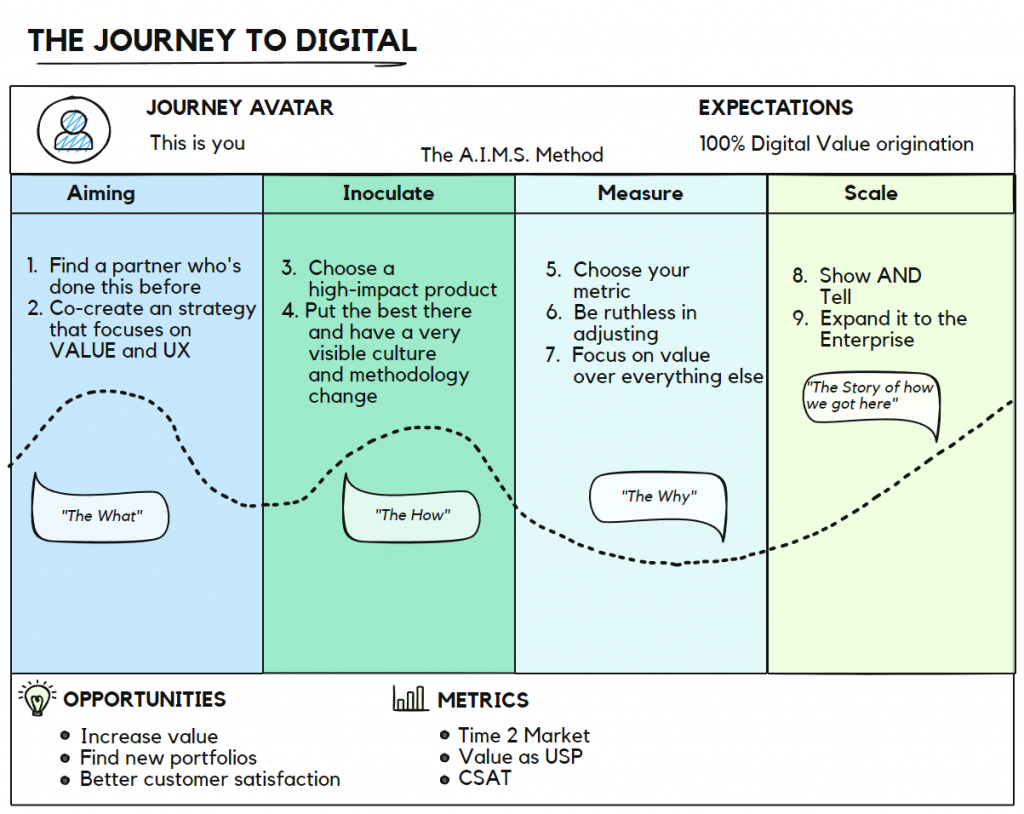

Transitioning an organization from traditional methods to SAFe Agile requires a well-planned approach that considers the organization’s unique context, culture, and existing processes. Here’s a high-level outline of steps to facilitate this transition:

1. Assess the current state: Begin by evaluating the organization’s existing processes, structures, and culture. Identify the strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for improvement that will help tailor the SAFe Agile implementation.

2. Create awareness and build leadership support: Educate organizational leaders and stakeholders on the benefits and principles of SAFe Agile. Secure their commitment to provide the necessary resources and support for a successful transition.

3. Identify and train change agents: Identify internal champions and change agents who will help drive the transition to SAFe Agile. Provide them with training and resources to effectively support and promote the adoption of the new framework.

4. Develop a transition plan: Create a detailed plan outlining the steps, timelines, and resources required to transition from traditional methods to SAFe Agile. This plan should include milestones, goals, and metrics to track progress and measure success.

5. Train and coach: Invest in training and coaching for employees at all levels, including executives, managers, and team members. Ensure that key roles, such as Release Train Engineers (RTEs), Product Owners, and Scrum Masters, receive specialized training to effectively perform their responsibilities within the SAFe framework.

6. Implement SAFe Agile incrementally: Start with a pilot project or a single Agile Release Train (ART) to test and refine the SAFe Agile implementation. Use lessons learned from the pilot to refine the approach before scaling it across the organization.

7. Adapt organizational structures and processes: Modify existing organizational structures and processes to align with SAFe Agile principles and practices. This may involve reorganizing teams, updating governance structures, and revising performance metrics and incentives.

8. Foster a culture of continuous improvement: Encourage a mindset of continuous learning and improvement throughout the organization. Regularly review progress, collect feedback, and adjust the implementation approach as needed.

9. Measure and evaluate progress: Track key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics to evaluate the success of the transition. Use these insights to inform ongoing improvements and adjustments to the SAFe Agile implementation.

10. Iterate and scale: Continue to refine the SAFe Agile implementation, incorporating feedback and lessons learned from earlier stages. Gradually scale the framework across the organization, launching additional ARTs and value streams as needed.

Transitioning from traditional methods to SAFe Agile can be a complex and challenging process. It requires a long-term commitment from the organization’s leadership and employees, as well as a thoughtful and strategic approach to managing change. By following these steps and remaining adaptable to the organization’s unique context and needs, organizations can successfully adopt SAFe Agile and realize its benefits.

What are the major challenges with SAFE Agile?

While SAFe Agile can be beneficial for many organizations, implementing and sustaining the framework can present certain challenges. Some of the major challenges associated with SAFe Agile include:

· Organizational resistance: Adopting SAFe Agile often requires significant changes to the existing organizational structure, processes, and culture. This can result in resistance from employees and management who are accustomed to traditional ways of working.

· Complexity: SAFe Agile is a comprehensive framework with multiple layers, roles, and processes. This complexity can be overwhelming for some organizations, especially those that are new to Agile methodologies. It may also lead to bureaucracy and reduced agility if not implemented effectively.

· Training and coaching: Successfully adopting SAFe Agile requires a considerable investment in training and coaching for employees at all levels of the organization. Finding the right trainers, coaches, and subject matter experts can be challenging and costly.

· Loss of team autonomy: SAFe Agile introduces higher-level structures and coordination mechanisms, which can sometimes result in a perceived loss of autonomy for individual Agile teams. This can lead to reduced motivation and engagement if not managed carefully.

· Balancing flexibility and standardization: SAFe Agile aims to provide a standardized approach to scaling Agile, but organizations must also maintain flexibility to adapt to their specific contexts and needs. Striking the right balance between standardization and customization can be difficult.

· Maintaining Agile principles: As organizations scale Agile practices using SAFe, it’s crucial to remain true to the core principles of Agile, such as collaboration, transparency, and continuous improvement. There is a risk of losing sight of these principles as the focus shifts towards managing large-scale processes and structures.

· Ensuring long-term commitment: Implementing SAFe Agile requires a long-term commitment from the organization’s leadership and employees. Failing to secure and maintain this commitment can result in suboptimal implementation and reduced benefits.

Overcoming these challenges requires a thoughtful and strategic approach to implementing SAFe Agile. Organizations should invest in training and coaching, foster a culture of continuous improvement, and remain adaptable to change. It’s also essential to ensure that the core values and principles of Agile are maintained throughout the scaling process. What does that means? It means that we’re talking about mindsets: Traditional Mindset vs. Agile Mindset.

The traditional mindset and the SAFe Agile mindset differ significantly in terms of their approach to project management, software development, and organizational culture. Here are some key differences between the two mindsets:

· Focus on process vs. value delivery: Traditional project management methodologies, like Waterfall, emphasize strict adherence to processes, detailed planning, and a sequential approach to development. In contrast, the SAFe Agile mindset prioritizes delivering value to customers through iterative, incremental, and adaptive processes.

· Predictive vs. adaptive planning: Traditional methodologies rely on upfront planning, where project scope, timelines, and resources are defined in detail at the beginning. The SAFe Agile mindset embraces adaptive planning, where plans are adjusted continuously based on feedback, learning, and changing conditions.

· Siloed vs. cross-functional teams: In traditional approaches, teams often work in silos, with each team focusing on a specific phase of the project. SAFe Agile promotes cross-functional teams that collaborate throughout the development process, resulting in more efficient and effective problem-solving.

· Fixed roles vs. shared responsibilities: Traditional methodologies assign specific roles and responsibilities to individuals, while the SAFe Agile mindset encourages shared responsibilities, collaboration, and self-organization among team members.

· Change resistance vs. embracing change: Traditional mindsets often view change as a risk, and any deviations from the initial plan may be considered problematic. In contrast, the SAFe Agile mindset welcomes change, viewing it as an opportunity to improve and adapt to evolving customer needs and market conditions.

· Contract negotiation vs. customer collaboration: Traditional approaches may prioritize contract negotiation and adherence to predefined requirements. On the other hand, SAFe Agile emphasizes collaboration with customers and stakeholders to better understand their needs and deliver valuable solutions.

· Command-and-control vs. servant leadership: Traditional management styles often involve top-down, command-and-control structures. The SAFe Agile mindset promotes servant leadership, where leaders empower, support, and enable their teams to make decisions and take ownership of their work.

· Linear vs. iterative development: Traditional methodologies follow a linear development process, moving from one phase to another in a sequential manner. SAFe Agile utilizes iterative development, where work is broken down into smaller increments, and each increment is developed, tested, and delivered in a short time frame.

· Focus on documentation vs. working solutions: Traditional approaches often prioritize comprehensive documentation over the delivery of working solutions. In contrast, the SAFe Agile mindset values working solutions and delivering customer value over extensive documentation.

· Risk avoidance vs. risk management: Traditional methodologies aim to avoid risks by following predefined processes and detailed planning. The SAFe Agile mindset embraces risk management by identifying, assessing, and addressing risks early and continuously throughout the development process.

These differences reflect the fundamental shift in mindset required when transitioning from traditional approaches to SAFe Agile. Adopting the SAFe Agile mindset involves embracing change, fostering collaboration, and focusing on delivering value to customers through iterative, adaptive processes.

This is very different than plain old Scrum, or Kanban. While SAFe incorporates both Kanban and Scrum, all this facets of its mindset manifest in a myriad roles.

Some of the SAFe roles are:

1.Team Level (the clear Scrum level):

· Agile Team: A cross-functional group of individuals, typically consisting of 5-11 members, responsible for defining, building, and testing features and stories within an iteration. The team typically includes a mix of developers, testers, and other specialists required to deliver the work.

· Scrum Master: Facilitates the Agile team’s process, ensures effective communication, removes impediments, and supports the team in adhering to Agile principles and practices.

· Product Owner: Represents the customer and stakeholders’ voice, manages the team’s backlog, and ensures that the team is working on the highest priority items to deliver value.

2.Program Level:

· Release Train Engineer (RTE): Acts as the chief Scrum Master for the Agile Release Train (ART), facilitating communication, collaboration, and coordination between the teams, and ensuring that the ART delivers value as planned.

· Product Management: Responsible for defining and prioritizing the Program Backlog, working closely with Product Owners and stakeholders to ensure alignment with the organization’s strategy and objectives.

· System Architect: Guides the technical aspects of the solution, ensures architectural alignment across teams, and collaborates with stakeholders to address technical dependencies and risks.

· Business Owners: Key stakeholders who have a vested interest in the outcomes delivered by the ART, providing guidance, prioritization, and feedback on the value delivered.

3.Portfolio Level:

· Lean Portfolio Management (LPM): A group of leaders responsible for strategy, investment funding, and governance, ensuring that the portfolio delivers maximum value while minimizing risks.

· Epic Owners: Drive the definition, analysis, and prioritization of epics (large initiatives), working closely with the LPM team to ensure that the organization is investing in the most valuable initiatives.

· Enterprise Architect: Provides guidance and support on the overall architectural vision, ensuring consistency and alignment across the entire portfolio, and promoting the reuse of architectural components.

In addition to these primary roles, SAFe Agile also includes other supporting roles, such as:

· DevOps Team: Collaborates with the Agile teams to ensure a continuous delivery pipeline, focusing on integration, testing, deployment, and release of software increments.

· System Team: Provides technical support, enabling environments, and tools to help the Agile teams in their development efforts.

· UX Designer: Collaborates with Agile teams to create user-centric designs, ensuring that the solutions delivered meet user needs and expectations.

Depending on the organization’s size and context, some of these roles may be combined or adapted as needed. It’s essential to ensure that each role is well-defined and supported by the necessary training and resources for effective SAFe Agile implementation.

All these roles combine into the juggernaut that is PI sessions. PI (Program Increment) sessions are mammoth affair that last two-three days and involve most of the Enterprise, once per quarter.

So, having going over all this complexity, what does a SAFe Enterprise looks like?

An organization that has successfully implemented SAFe Agile exhibits certain characteristics across its processes, structures, and culture. These characteristics indicate that the organization has embraced the core principles and practices of the Scaled Agile Framework. Here’s what such an organization typically looks like:

· Aligned teams and value streams: The organization has identified its value streams and formed Agile Release Trains (ARTs), which are cross-functional teams that work together to deliver value incrementally. These teams are aligned with the organization’s strategic goals and priorities.

· Program Increment (PI) cadence: The organization follows a regular cadence of Program Increments (PIs), which include PI Planning, execution, and Inspect and Adapt (I&A) events. This cadence provides predictability and enables continuous improvement.

· Collaborative culture: The organization fosters a culture of collaboration, open communication, and transparency among team members, across teams, and with stakeholders. This encourages the sharing of ideas, knowledge, and feedback, leading to better decision-making and problem-solving.

· Lean-Agile leadership: Leaders in the organization practice servant leadership, empowering their teams to take ownership of their work and make decisions. They support continuous learning, innovation, and process improvement.

· Adaptability and responsiveness: The organization is able to adapt and respond to changing customer needs, market conditions, and new information quickly and effectively. It embraces change as an opportunity to learn, grow, and deliver better solutions.

· Focus on customer value: The organization prioritizes delivering value to customers and continuously seeks to understand and meet their needs. This focus on customer value drives decision-making and resource allocation.

· Continuous improvement: The organization promotes a mindset of continuous learning and improvement, regularly reviewing and adjusting its processes, structures, and culture to optimize performance and outcomes.

· Lean Portfolio Management (LPM): The organization practices Lean Portfolio Management to align strategy, funding, and execution across the portfolio. This ensures that investments are focused on delivering maximum value while minimizing risk and dependencies.

· DevOps and Continuous Delivery: The organization has integrated DevOps practices and established a continuous delivery pipeline, enabling faster, more reliable, and more frequent releases of software increments.

· Metrics-driven decision-making: The organization tracks key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics to evaluate its performance, identify areas for improvement, and inform decision-making.

An organization that has successfully implemented SAFe Agile will exhibit these characteristics, demonstrating its commitment to the principles and practices of the framework. This enables the organization to achieve better alignment, collaboration, adaptability, and ultimately deliver greater value to its customers.

Should you go SAFe? The Fede’s Five Question for SAFety

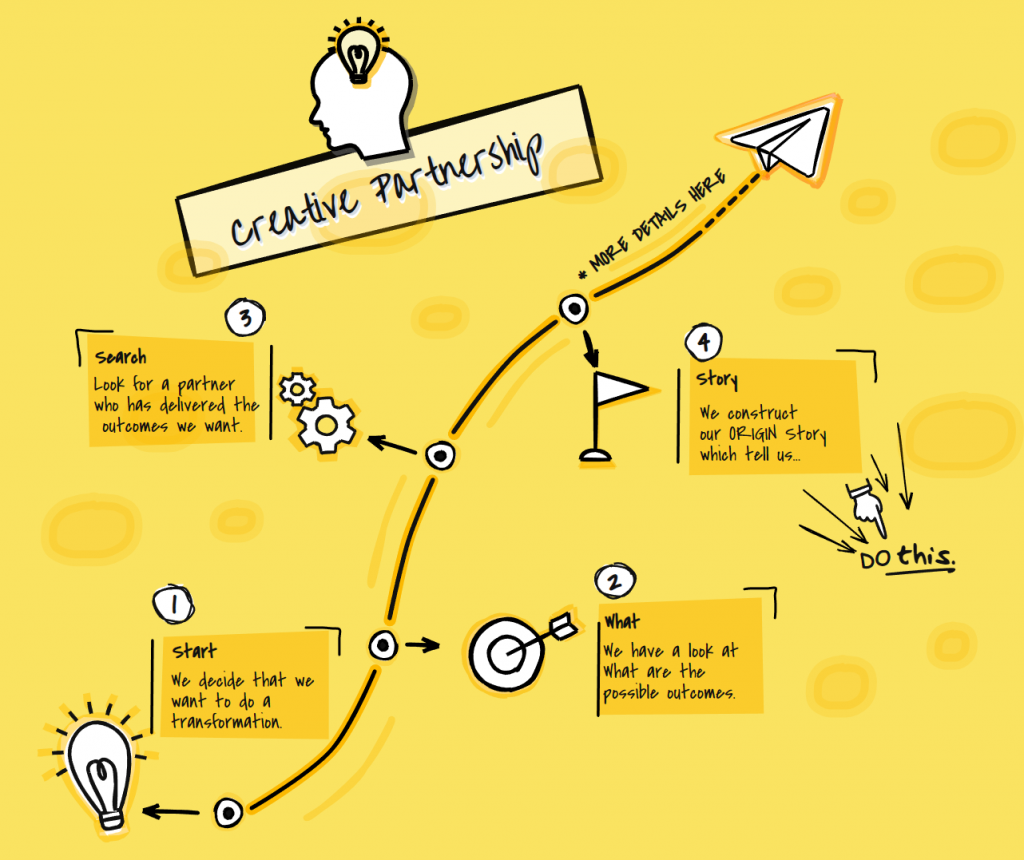

Having said that, we go back to the first question. Should you go SAFe?

This is a question that’s difficult to answer in a yes/no manner. So I have five questions that I use, Fede’s Five if you will. They are not a binary, but the five of them together will help clarify things.

1. Size does matter: If your Enterprise is not above 300+ people, there is very little incentive to go to SAFe. While there are lightweights applications of SAFe, it is designed for a very large number of people in multiproduct Enterprises. Plain Scrum or the Spotify/ING model might be better suited. If you have the numbers, SAFe has the roles for them.

2. Multiproduct: SAFe thrives on the Lean Portfolio Management system, that created streams for multiple products. If you have just one main product, either LeSS or Spotify might be better (more on those models soon!). But if you have a multiproduct situation, SAFe will help tremendously to organize the streams.

3. Your products are not mostly push-demand oriented: if your business model is based on SLAs and L3 service, SAFe’s PI planning and long-term roadmaps might hinder more than help. But for stable institutions that seek to become more Agile, like Banks, SAFe can be the right medium.

4. You have people working on culture and mindset: Any Agile transformation will produce some resistance. I don’t care if you’re the most charismatic individual, you will need people thinking and dealing with the changing mindset via coaching, interventions, workshops, etc. If you do not have people working on that, a less-impactful transformation at first can help convince stakeholders of the need for them.

5. Finally, you have some experience in Agility in your Enterprise, don’t you?: SAFe runs on Kanban, Lean and Scrum, while adding its own twists. In the case you haven’t got to a comfortable level with any of these methodologies please run a PoC with them first. Trying to learn and implement all three while juggling SAFe also is doomed to fail. But if you have, SAFe provides a stable, proven framework for the next level of transformation.

There you have it: my approach to SAFe in…well, not a nutshell, but certainly less than what is the usual length of text. I hope this has been useful and let me know in the comments if there’s anything you would add or change!